- Home

- Karen Tumulty

The Triumph of Nancy Reagan Page 7

The Triumph of Nancy Reagan Read online

Page 7

By Nancy’s senior year at Smith, the war abroad defined almost everything about life at home. Existence was regimented by Meatless Mondays, gasoline rationing, air-raid drills, blood drives. Women of Smith shoveled their own snow and did without their customary maid service. They looked askance at those who left coffee in their cups or precious butter on their plates. Some of Nancy’s classmates helped out local farmers, who were hard pressed by labor shortages. Smith women picked their asparagus and weeded their onions.

There were fewer beaus at the ready to take them out on Saturday nights. In their stead came letters from overseas, which arrived with a censor’s stamp. Campus housing and classrooms were bursting at the seams, owing to the fact that much of Smith had been turned over to the first classes of officers for the US Naval Reserve’s women’s branch, better known as WAVES, an acronym for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. A new class of five hundred female midshipmen arrived every month for sixty to ninety days of strenuous training. As the WAVES marched by silently in their uniforms to classes and meals, Smithies noticed themselves standing a little straighter.

Another of Smith’s contributions to the war effort—one in which Nancy participated—was the Factory Follies. This was a thirty-three-woman morale-boosting musical troupe that entertained at lunch and break time in more than a dozen war plants across the Connecticut River Valley. Their revue, which toured in the spring of 1943, opened with a chorus marching across the stage, singing:

Make with the maximum, give with the brawn.

Make with the maximum, smother that yawn.

Tell the boys we’ll stand behind ’em till the lights come on.

And we’ll make with the maximum.

Make with the maximum, give with the brain.

Make with the maximum, gonna raise Cain.

Tell the boys in boats and tanks, tell the guy who flies a plane.

That we’ll make with the maximum.

Switch on, contact, turn on the juice,

Double the output, and here’s my excuse:

Life can be pretty when you’re being of use.

Hey! Fellas! We’ve gotta produce.

Nancy played the sophisticated “Glamour Gal,” a shirker on the production line. Glamour Gal lamented that she missed her prewar life of luxury:

Maybe you’re right

But the yacht was fun,

Cocktails at five and

Dinner at the Stork,

Long drives in the country,

To get away from New York.

Nancy also acted in a few plays on campus, including a musical comedy called Ladies on the Loose. At one of the college’s annual Rally Day shows, she and her classmates tap-danced in Morse code, and sang: “Dit-dit-dit-dah! We’ll win this wah.” But Smith was not known as a training ground for serious actresses. She was one of only three theater majors in 1943. The college did not even have a full-fledged theater department until her senior year. The closest thing Nancy got to actual professional experience was on summer breaks, when she apprenticed on “the straw-hat circuit” doing summer stock in Wisconsin and New England. She cleaned dressing rooms, painted scenery, sold tickets, and tacked up flyers around town. Only rarely did she get to act. In her three years of summer stock, Nancy delivered a total of one line—“Madam, dinner is served”—when she played a maid in a production starring Diana Barrymore, a lesser member of the famous theater family.

In 1941 Nancy worked at the Bass Rocks Theater in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she developed what she remembered as a “big crush” on one of its visiting stars, Buddy Ebsen. He would become most famous for his starring role as Jed Clampett in the 1960s TV sitcom The Beverly Hillbillies, but at the time, Ebsen was known for movies that put his dancing talent to use. Backstage, Nancy was so entranced by one of his performances that she forgot her own task, which was to turn on the musical sound effect when his character pretended to play a Victrola. Nancy realized her mistake, fumbled, and started the tune late, then rushed out of the theater in tears. Ebsen “followed me outside and told me it was all right, not to worry, and the world was brighter again,” she said. As starstruck as she obviously was, Nancy in later life downplayed the idea that she’d ever harbored serious ambition: “When I graduated, I went on to become an actress, not really because I wanted a career. I was never really a career woman, but only because I hadn’t found the man I wanted to marry. I couldn’t sit around and do nothing, so I became an actress.”

May commencement ceremonies for the 408 women of the Smith College class of 1943 were somber and spare. Bowing to shortages and to the national mood, the college dispensed with the gayest of its traditions. There was no parade of colorfully dressed alumnae waving placards with witty slogans, no procession of juniors with a train of ivy on their shoulders, no roses carried by the seniors. Attendance was limited to parents and families of the graduates, who had to stay in the dorms because there was nowhere else to house them. Loyal, still stationed in Europe, did not make it back for the ceremony; nor, apparently, could Edie, because of wartime travel restrictions that gave priority on trains to military personnel. The college did broadcast a special program from Smith president Herbert Davis’s house. “The class of 1943 did not go, as commencement orators used to be fond of saying, out into the world. For four years, they have participated, as students, in a world at war,” the announcer said. “They are not leaving the little world for the great world; they have lived in the great world all along.”

On graduation day, about twenty-five members of Nancy’s class were already married, and a greater number were engaged to be. She herself was dating a wealthy Amherst College boy off and on. Just over a year later, in June 1944, Nancy announced her plans to marry James Platt White Jr., who by then was stationed on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific. “The young couple met during their college days and renewed their friendship when Navy orders took Lieutenant White to Chicago,” the city’s Daily News noted. “Both brunette, they made an attractive couple at parties and benefits during the year in which he was stationed in Chicago on the aircraft carrier Sable.” When her godmother Nazimova was introduced to Nancy’s fiancé over dinner, he made a strong impression. Nazimova wrote in her diary: “I think I met one of our great future statesmen, perhaps even a president.”

Their intention was to be married when the war ended, but Nancy abruptly canceled the engagement shortly after it was announced. “It was a heady, exhilarating time, and I was swept up in the glamour of the war, wartime engagements, and waiting for the boys who were away. I realized I had made a mistake. It would have been unfair to him and to me. It wasn’t easy to break off the engagement, but it was the best thing for us both. We were not meant to be married, but we remain friends,” she wrote in her 1980 memoir.

Her brother has a different explanation: when White came home on leave, Nancy discovered he was homosexual. White “was extremely handsome and was a naval aviator, and they had, sort of, a rendezvous or a pre-engagement party in California, when she found out he was gay,” Dick Davis told me. This discovery was not something Nancy ever discussed with her stepbrother. “Edith told me, actually. Edith would know things like that, you know, about everybody,” he said.

After Nancy became a nationally known political figure, her past romantic life was a sensitive subject. Dick said she “went to great trouble when she got to the White House” to make sure that no one ever learned the truth about the breakup of her first engagement. White, who became a partner in a New York City importing firm, was discreetly silent about their long-ago betrothal. “All I can tell you, all I will tell you, is that Nancy was a lovely, lovely girl. It was just one of those wartime things,” he told Parade magazine in one rare interview. When White became seriously ill, he got in touch with the nation’s first lady indirectly through her friend Jerry Zipkin, a fixture on the New York City social scene who was also gay. It was through Zipkin that Nancy learned White had died.

From the time she was a young w

oman, many of Nancy’s closest friends were gay. “Nancy’s affinity for homosexual men has been frequently remarked upon, but it would hardly have been so noteworthy if she had stayed in show business instead of marrying an actor who went into politics. She was close to a number of lesbian and bisexual women over the years, starting with her godmother and her circle of friends, but this, too, is not unusual in the entertainment world,” biographer Colacello noted. “If gay men were attracted to the young Nancy Davis, it was probably for the same reasons that straight men were: she was pretty, lively, well dressed, a good dancer, a great listener, and, like her mother, a natural-born coquette. She knew how to flirt with a man in a way that was flattering and unthreatening, which may explain why gay men felt especially comfortable with her. And when she was out with a man, she gave him her full attention.”

* * *

Having broken her engagement in the summer of 1944, Nancy once again found herself confronting an uncertain, unmoored future. She had returned to Chicago after her graduation to be with her mother while Loyal remained overseas. Edie had temporarily sublet the Lake Shore Drive apartment and moved into the Drake Hotel, no doubt to lift some of the strain on their finances. Nancy looked for ways to fill her days. She joined the Chicago Junior League and volunteered twice a week at the Service Men’s Center, the military social club that her mother had helped set up. She also worked as a salesgirl at Marshall Field’s, Chicago’s flagship department store. It was an experience memorable mostly for the time she chased down a female shoplifter she had spotted slipping a piece of jewelry into her purse. Nancy also trained as a nurse’s aide at Cook County Hospital. Her first patient died as she was giving him a bed bath, something Nancy didn’t realize until she asked a medical resident why the sick man’s skin had gotten so oddly cold on a hot day.

Nancy was growing restless and bored. Her salvation came when she received a call from her mother’s famous friend ZaSu Pitts, a comedienne with doleful eyes and a warbly voice, who was known for playing ditzy characters. Pitts was taking her Broadway play Ramshackle Inn on the road and offered Nancy a tiny part. It did not take much acting skill. She played a girl who was kept in the attic, except for one scene in which she burst onto the stage and said three lines. Though a small start, Nancy was grateful and recognized her good fortune was not of her own doing. “This wouldn’t be the last time I benefited from Mother’s network of friends in show business,” she wrote. “I don’t think I would have had much work as a stage actress if it hadn’t been for Mother. There was just too much competition, and I didn’t have the drive that Mother had.”

She joined the cast in Detroit. Reviews of the production were brutal, but audiences turned up anyway to see Pitts. It “played eight months in New York and two years on the road despite the disdain of most critics,” a Boston newspaper noted. As Ramshackle Inn made its way across the country, Nancy and Pitts became close. The star shared her hotel rooms and dressing rooms with the young actress, who became her protégée. They eventually ended up back in New York, and the play closed in the summer of 1946.

Nancy decided to stay in New York and try her luck there. For a twentysomething just after the end of World War II, there could hardly have been a more exciting place to live than Manhattan. With other world capitals in ruins, Gotham took on a swagger. Scarcity and sacrifice were suddenly things of the past. An unprecedented building boom was under way. The nightclubs and theaters were packed. Broadway was at the dawn of a golden era. But finding her own way to the footlights was a challenge and an ordeal. Nancy modeled a bit, took acting and voice classes. She forced herself to show up for auditions that she found “frightening and embarrassing” but did not land many parts. She was fired from one she did get, on the third day of rehearsal. The director told her, “It’s just not working.”

The only Broadway role she ever snagged was playing a lady-in-waiting named Si-Tchun in the 1946 musical Lute Song. That production would be remembered as the first big break for a young Russian-born actor named Yul Brynner. Nancy was not among his fans. “All the girls were so crazy about Yul. One young girl I remember committed suicide over him,” Nancy told interviewer Judy Woodruff of PBS. “I wasn’t too impressed, really. Every time he’d tell a story about his background, it always changed.”

Nancy had read for the part in producer Michael Myerberg’s office. “After all of the tryouts, readings, refusals, and waiting for refusals by telephone, it was unbelievable how swift and easy it was when I heard the magic words, ‘You’ve got the part,’ ” she recalled. But she was puzzled when the producer added: “You look like you could be Chinese.” The real story was that the show’s leading lady—Mary Martin, another of Edie’s friends—had demanded Nancy be given the job. Martin intervened again when the director John Houseman tried to get rid of Nancy during the early weeks of rehearsals. She had dyed her hair black but was unconvincing as a Chinese handmaiden. “John,” his star told him, “I have a very bad back, and Nancy’s father Loyal Davis is the greatest [neurosurgeon] in the USA. We are not letting Nancy go.” Only later, in Houseman’s memoirs, did Nancy learn that her first big break was not due to her talent. Houseman wrote that he had offered her the role through “the usual nepotistic casting.… At Mary’s behest, to play the princess’s flower maiden, we engaged a pink-cheeked amateurish virgin by the name of Nancy Davis.”

When Lute Song closed after only four months, ZaSu Pitts came through with parts for Nancy in two more plays, one of which was a touring revival of a comedy called The Late Christopher Bean. An August 1947 review of an early performance at the Saratoga Spa Playhouse in upstate New York takes note near the end of “a Miss Nancy Davis, who looks wholesome as a ripe red apple, even though little is required of her except to be the decent one of the two Haggett daughters.” Nancy pasted her reviews, even tepid ones, into her scrapbook, along with congratulatory cards and telegrams. Many were from famous names such as the Tracys and the Hustons. Others were not so well known, but meaningful. One note, delivered with flowers for the Chicago opening of Christopher Bean, was from the lawyer and Lake Shore Drive neighbor who had helped arrange Nancy’s adoption by Loyal. It said: “To my adorable Nancy from your general counsel and greatest admirer, Orville Taylor.”

Her life in a fourth-floor walkup at 409 East Fifty-First Street had its frustrations, but it was not exactly one of hardship. Nancy got around on the crosstown bus and felt safe walking home through Midtown Manhattan late at night. Loyal and Edie kept her afloat financially. Though she was a young, single woman, Nancy was drawn to her parents’ mature circle of friends, who helped keep her occupied. “Fortunately, I wasn’t entirely alone in the big city. When I was living on East Fifty-First Street, the Hustons had an apartment around the corner. Lillian Gish, another family friend, had one nearby. They often took me out to eat or to a show, or had me over to little parties,” she recalled. “I used to go watch Spence rehearse for a play he was opening in, The Rugged Path. He was very nervous about returning to the stage, but he was very good, as he always was.” Tracy’s mistress Katharine Hepburn, who lived on East Forty-Ninth Street, had an aversion to going out and often invited Nancy over to keep her company.

Nancy also dated, though no one exclusively. Her social life intertwined with her professional ambition. Nancy kept company with Max Allentuck, a prominent theater manager who worked with some of the biggest producers of the era; they remained friendly enough that in 1981, when one of his plays came to Washington, she invited him to lunch and to tea at the White House. Her most frequent companion was Kenneth Giniger, the publicity director at publisher Prentice Hall. This friendship was another of Edie’s arrangements. Giniger sometimes booked his authors for interviews on a midmorning radio show that Edie hosted in Chicago. When Edie suggested he look up her daughter in New York, he did. Giniger took Nancy to see-and-be-seen nightspots such as the Stork Club and El Morocco, and made sure her name popped up occasionally in the newspaper columns.

One day in the fall

of 1948, Edie called her daughter to let her know that if she heard from someone who said he was Clark Gable, she should not assume it was a prank. The movie star known as the “King of Hollywood” was coming to New York, and Spencer Tracy had given him Nancy’s number. Sure enough, Gable called, and the two of them went out every day for a week, usually ending up at the Stork Club. Gable charmed Nancy; he sent flowers, and they held hands. “He had a quality that good courtesans also have—when he was with you, he was really with you,” Nancy recalled later.

This was never a serious romance, however. The Gone With the Wind star was twenty years older than Nancy and in a rocky phase of his life. Gable was drinking too much, was having a string of affairs, and had never truly gotten over the death of his third wife and soulmate, actress Carole Lombard, in a 1942 plane crash.

Still, being seen with him created a brief and welcome stir around Nancy. The movie magazines and gossip columns buzzed with speculation about the famous star and the unknown actress. Those clippings, too, made it into Nancy’s scrapbook. Typical was one that said: “At the party in New York that Tommy Joyce gave in honor of Clark Gable and Walter Pidgeon, Clark arrived with Nancy Davis on his arm. Nancy, according to my informant, is a beautiful little brunette. Clark gave her the typical Gable treatment, devoting himself to her—so much so that some of the people present said, ‘This is it!’ ” Another, apparently from a Chicago newspaper, reported: “A twosome that has New York agog is our Nancy Davis and the great Clark Gable who are seen together hitting the night spots every evening. Nancy is the beautiful and talented daughter of Dr. and Mrs. Loyal Davis.” Probably closest to the truth was what Dorothy Kilgallen wrote in her syndicated column, The Voice of Broadway: “Nancy Davis, the lass who dated Clark Gable so often on his last visit here, wasn’t unhappy about the resulting publicity. She has theatrical ambitions.”

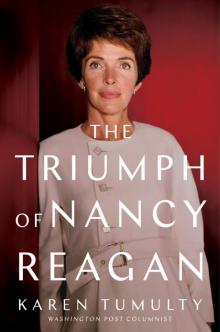

The Triumph of Nancy Reagan

The Triumph of Nancy Reagan